How a one-page profile can help people with dementia reconnect with their past, recall happy memories and make decisions about who they want to spend time with and what would make them happy.

Written by: Gill Bailey

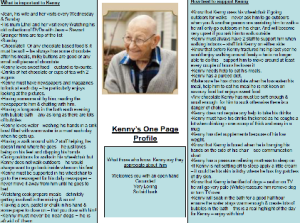

Ninety-two year old Winifred Baguely can be heard singing and laughing as she helps the housekeeper out with her daily routines at Bruce Lodge where she lives. Winifred, who has dementia has always been warm, loving and generous but she hasn’t always been this satisfied and relaxed in her new home; until she produced a one-page profile with dramatic effects.

One-page profiles for both staff and people living at Bruce Lodge were introduced to achieve two things. For staff, it enabled a greater understanding of each other and meant that each week team members spent time away from their day to day activities to do something that they personally felt was an important part of their role. For the people living there with dementia, the one-page profiles acted as a job description, allowing them to direct their own support and ensuring that the people providing the support understood what was important to them.

All staff at Bruce Lodge, including housekeepers and maintenance staff, produced their own profiles. This exercise allowed the people living with dementia to be matched well with the staff team and choose who they wanted to spend extra time with based on their interests and what was important to them. Winifred chose to spend her time with Beryl the housekeeper because she said she enjoyed helping out with the daily chores such as polishing, sweeping and mopping. Winifred’s two daughters and staff at Bruce Lodge helped uncover this by sitting down with her and chatting over tea and biscuits to inform the one-page profile. They asked about good days and bad days, past and present. What was going well and what needed to change. What Winifred had enjoyed in her life in the past, and what she would do, if she could, in the future.

Winifred’s new relationship with Beryl and extra responsibility has had an extraordinary effect on her happiness and wellbeing. At home she would routinely clean the house, so before this was identified in the one-page profile as being important to her, a big part of her life and identity had been missing.

Maureen and Bernie, Winifred’s daughters, have noticed the change that the one-page profile has made to Winifred. She is happier, chatting more, using fuller sentences, sleeping better and is generally ‘’more alive’’. Maureen goes on to say; “The difference is astounding; mum was a housewife, a practical person who spent her life caring for her five children and our father, who died 20 years ago. Her desire to care for people was never blunted but the ability to do so was robbed from her and that left her very frustrated. These chores are helping her connect with other things from her past and are opening up new pathways in her mind. The first thing that we noticed had come back was her language – within a week of working with Beryl she was recalling words much better and introducing me to other people by name, whereas before she didn’t know who I was.”

Winifred now has enhanced choice and control over how she lives her life and how she is supported on a day to day basis. Winifred can often be found well into the evening, long after the housekeeper has gone home, sitting and folding the laundry. This has simply become the way she chooses to spend her time and the impact this has had on her happiness is evident for all to see. Not only is her smile lighting up her own room but she can be seen beaming all over the home as she reconnects with what she loves most; helping to look after others and bringing joy to the people she lives with.